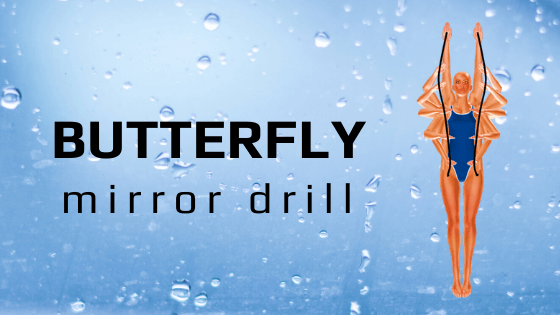

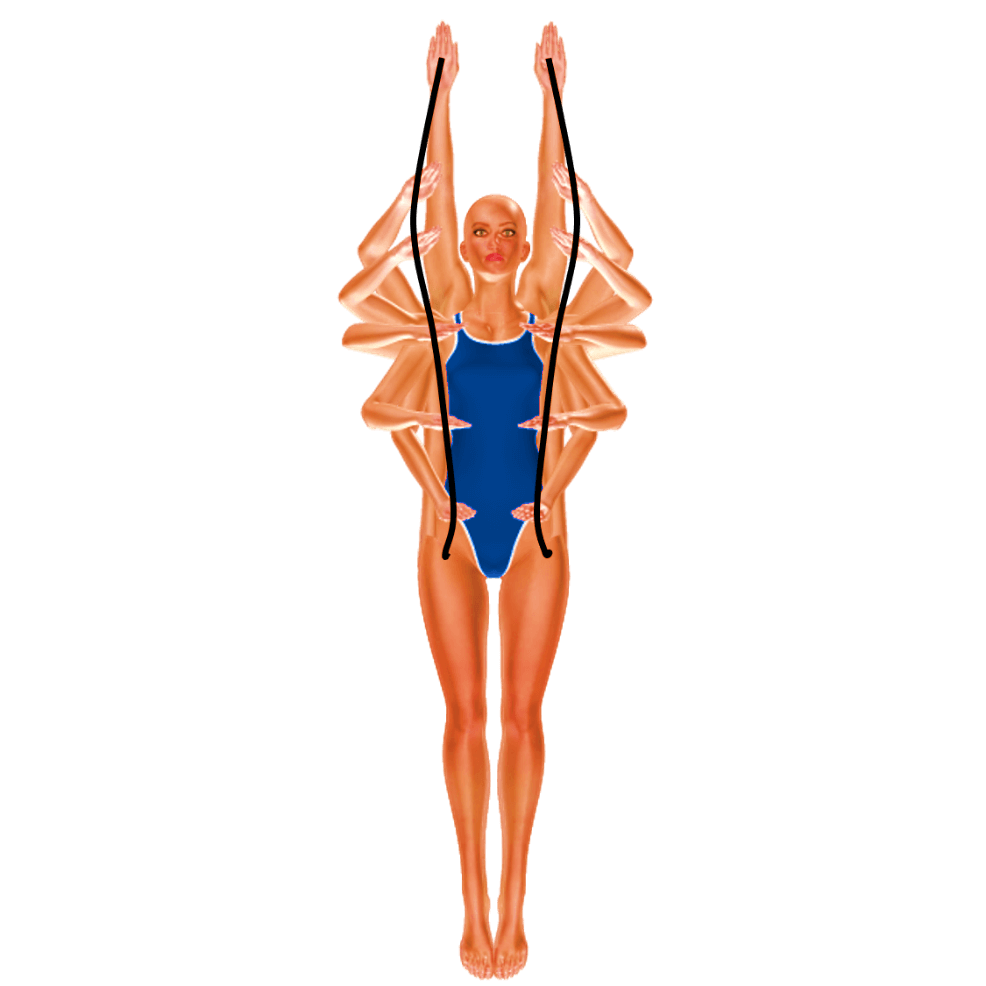

Butterfly Mirror Drill

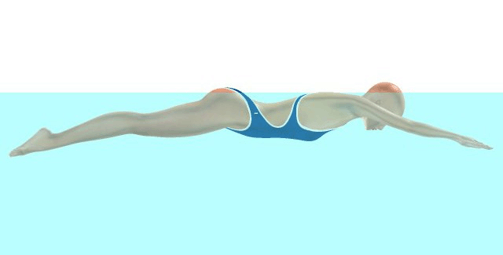

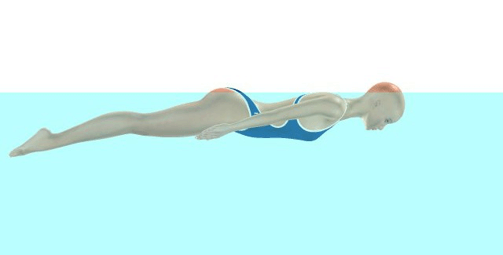

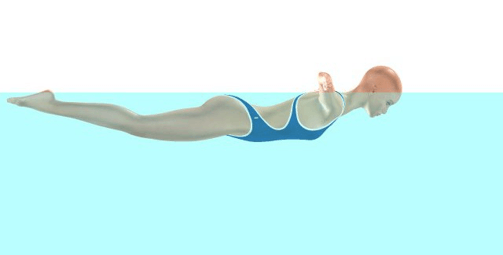

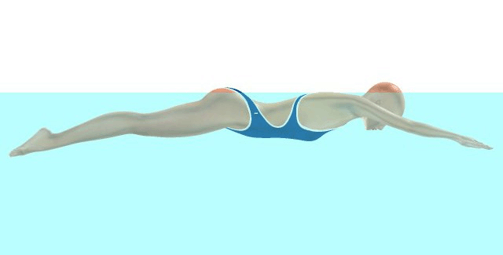

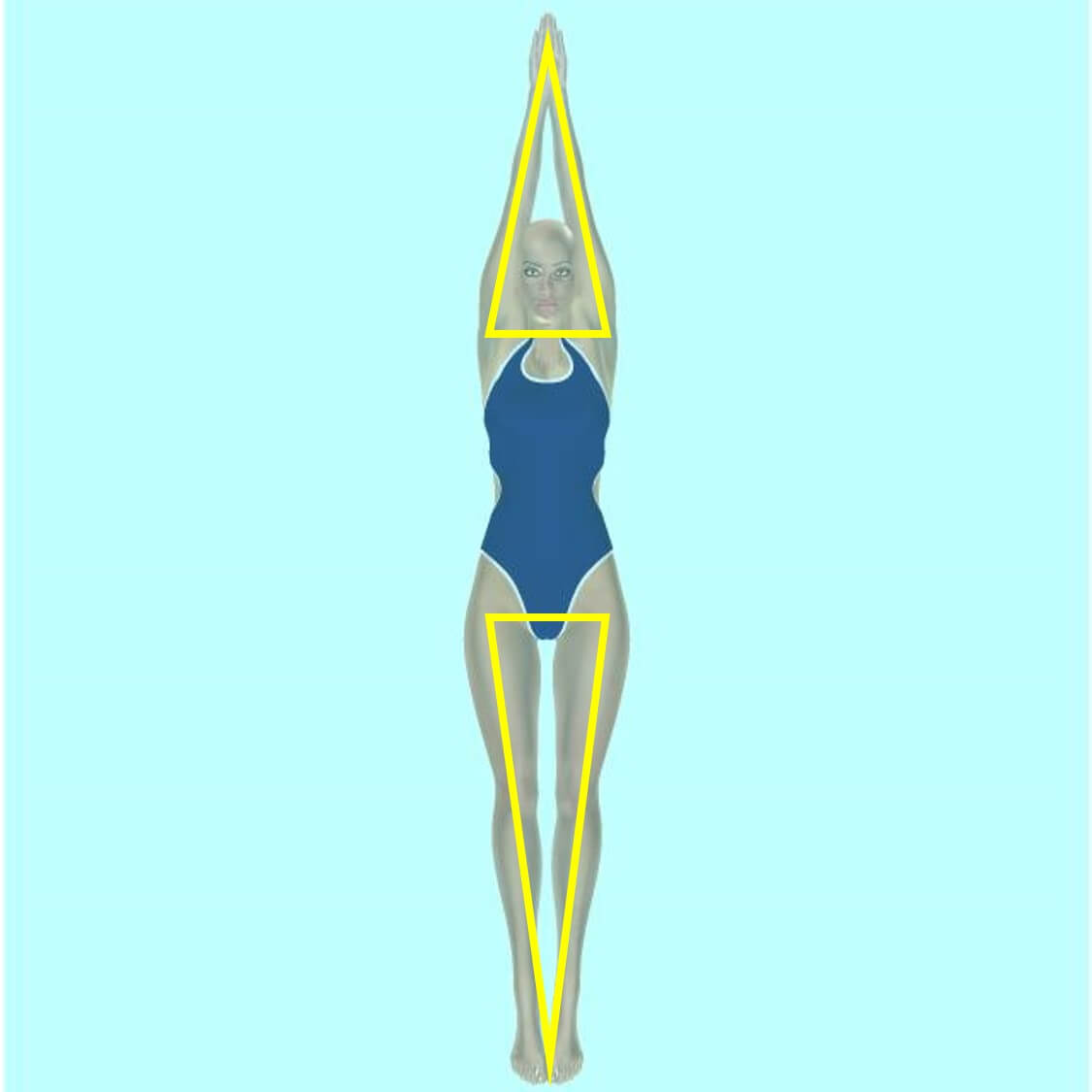

The image below shows the optimal, underwater arm motion for butterfly. The black lines show the path of the hands. To replicate this motion, stand in front of a mirror with the arms straight and directly above the shoulders. Then perform the 7 steps listed. Move the arms very slowly at first, watching the arms in the mirror. Practice at a slow speed until you’ve mastered the motion. Then, slightly increase the speed of the arms and again practice until mastered. Keep practicing with small increases in the speed of the arms until they are moving at normal swimming speed.

- To begin the pull phase, flex the elbows.

- Watch the hands move slightly apart but keep them inside the elbows.

- Keep flexing the elbows until the hands are in the same plane with the shoulders.

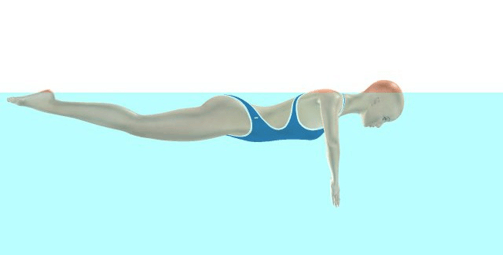

- To begin the push phase, push the hands toward the legs.

- Extend the wrists as the arms straighten so the palms face down.

- As the elbows lock, touch the front of the thighs with the thumbs.

- Move the palms along the sides of the legs and then recover the arms to the starting position.

While it may feel natural to begin the arm motion by moving the hands to the sides, this puts the arms in a weak position. To increase the strength of the arm position, begin the arm motion with elbow flexion.

The butterfly hand path has often been described as a “keyhole,” and consequently, sideways motion is usually exaggerated. The hand path in the image is better described as “a very narrow keyhole.”