What does the index of coordination (IdC) have to do with swimming faster?

The IdC is a measure of arm coordination in freestyle. Specifically, the IdC indicates if the arm coordination is less effective by producing gaps in propulsion or if the arm coordination is more effective by producing a more consistent source of propulsion. The main benefit of more continuous propulsion is faster swimming.

An effective freestyle with “no gaps in propulsion” has been supported by research since at least 1955 (Counsilman). Since then, numerous other studies concluded that gaps in propulsion were counterproductive and should, in fact, be considered a technique error (e.g., Chollet, Millet, Lerda, Hue, & Chatard, 2003; Schnitzler, Ernwein, Seifert, & Chollet, 2006; Seifert, Boulesteix, & Chollet, 2003).

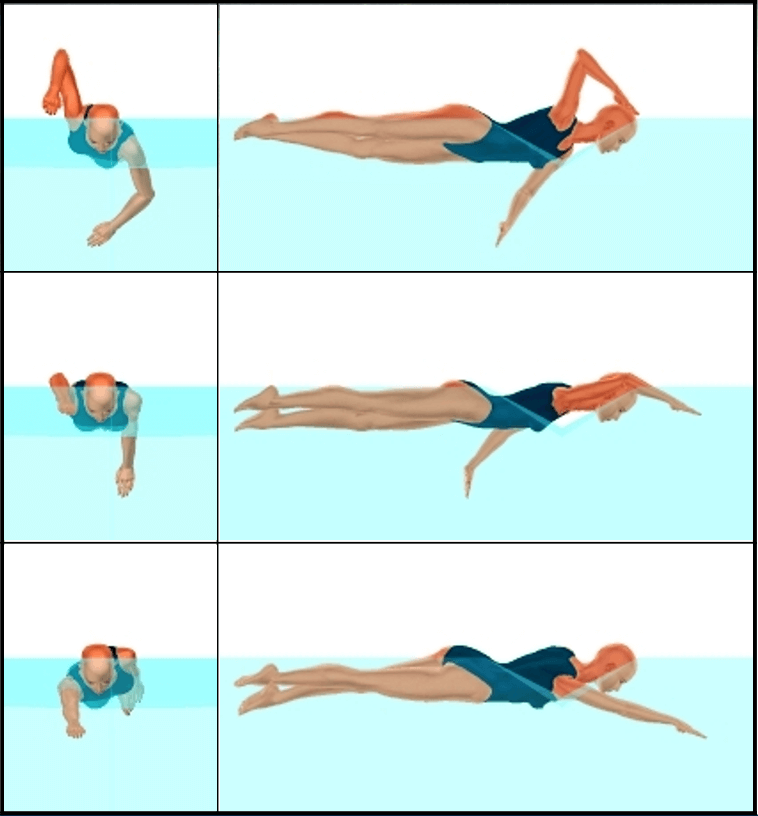

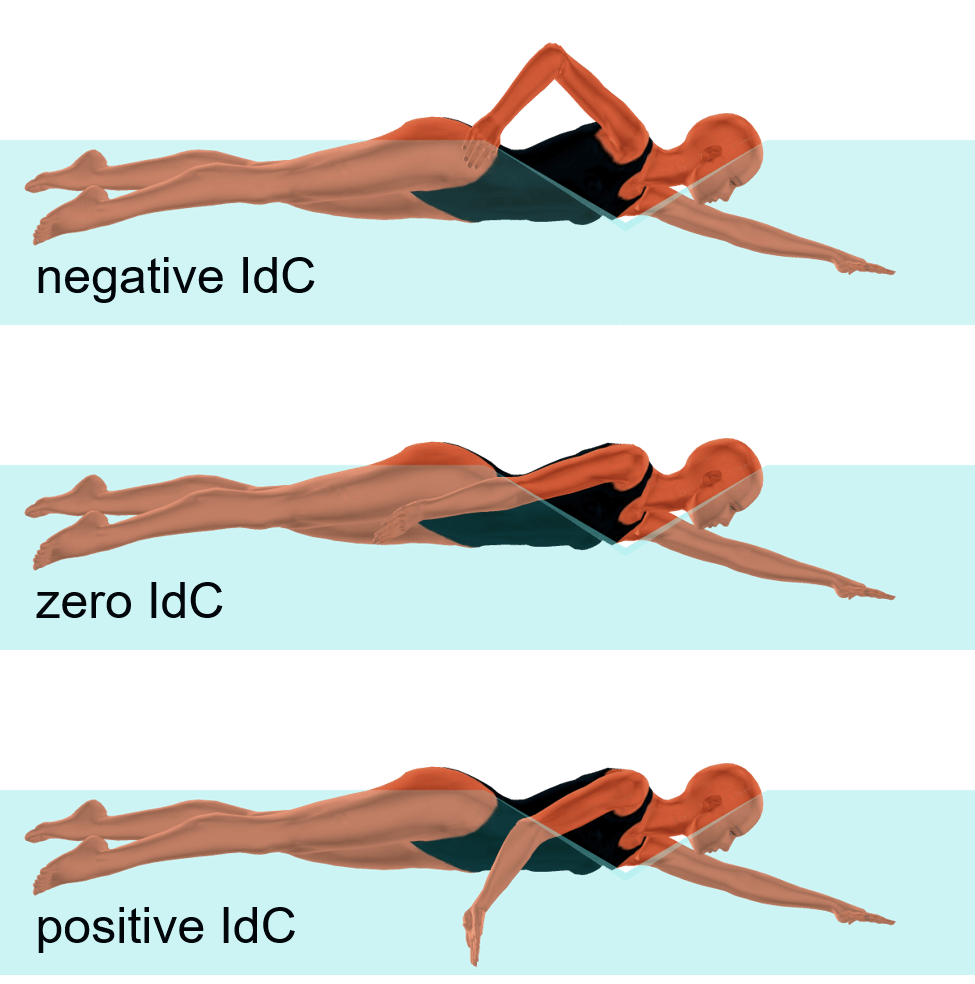

The IdC was developed in 2000 to quantify the relative position of the arms throughout the stroke cycle, (Chollet, Chalies, & Chatard). A zero IdC occurs when one hand begins to pull at the same time that the opposite hand completes the push (middle image). With a zero IdC, the arms are in opposition throughout the stroke cycle.

A negative IdC occurs when the entry arm does not begin to pull when the opposite arm completes the push (top image). The failure of the entry arm to begin to pull causes gaps in propulsion. A negative IdC is also called catch-up stroke.

A positive IdC occurs when the entry arm begins to pull before the opposite arm completes the push (bottom image). A positive IdC is also called superposition, as there is an overlap in arm propulsion for a more continuous source of propulsion.

The science overwhelming supports a positive IdC for the fastest swimming. Yet, swimmers are almost always using a negative IdC, often -5% to -10% and even lower. A swimmer cannot maximize velocity with a negative IdC.

Swimmers usually only use a positive IdC at velocities above 1.8 m/sec. Even at the fastest swimming velocities (over 2.0 m/sec), an IdC above 5% is rare. An IdC over 10% and probably over 20%, however, is possible and also essential for the fastest human swimming.

Unfortunately, typical training promotes a negative IdC. Swimming longer distances at a slower stroke rate, fatigue, and an arm entry parallel to the water surface all encourage a delay in beginning propulsion with the entry arm. The result is that swimmers are usually practicing an arm coordination that is counterproductive to swimming fast.

Fortunately, there are strategies that can help a swimmer learn to swim with a positive IdC and make use of the arm coordination that produces the fastest swimming. Optimizing the IdC requires 1.) mastering an effective downward angle on the arm entry, 2.) maintaining primarily backward hand motion as the torso rotates upward on the push phase, and 3.) gradually increasing the speed of the arm recovery with an increasing stroke rate. Any swimmers who hope to optimize performance would do well to evaluate their own IdC and work to improve it.

Interested in IdC? Follow the links below to learn more!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DYn51lJxO6U

https://www.iat.uni-leipzig.de/datenbanken/iks/bms/Record/4019193

https://www.iat.uni-leipzig.de/datenbanken/iks/bms/Record/4032674