5 Things Your Mother Told You About Swimming Technique

We’ve all grown up with an expression or two seared on our brains. You know what I’m talking about! Expressions like “Haste makes waste,” or “You can’t judge a book by its cover.”

There are a few of those sayings that make sense today when thinking about them in terms of swimming technique. (OK –probably not exactly what your mom was thinking but maybe an easy way to grasp a few really important concepts and remember them when you are in the water.)

So, in no particular order:

1. You snooze, you lose.

I’m going to lay off the science on this one because there are almost 50 years of research – from Doc Counsilman to Ludovic Seifert – that definitively prove that catch-up stroke has no business in a competition pool. Instead, just close your eyes and visualize taking your best freestyle stroke and then holding your arm/hand outstretched until your other hand catches up with it. What just happened? Were you resting for just a moment? Yes. You were! And while you were “snoozing” you were “losing” velocity. You were also delaying the beginning of your next stroke (creating a gap in propulsion https://swimmingtechnology.com/injury-prevention-rehab/freestyle-arm-entry-stress/ ) while adding stress to your shoulders. If you want to swim fast, you’ll need to go in the opposite direction: start your next stroke before you’ve finished with the first one. (i.e. begin the pull before you finish the push. The scientific term for this is positive “Index of Coordination” or positive IdC.)

2. Keep your head up.

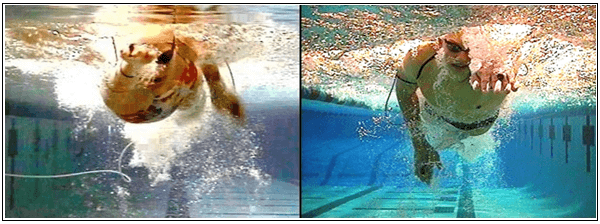

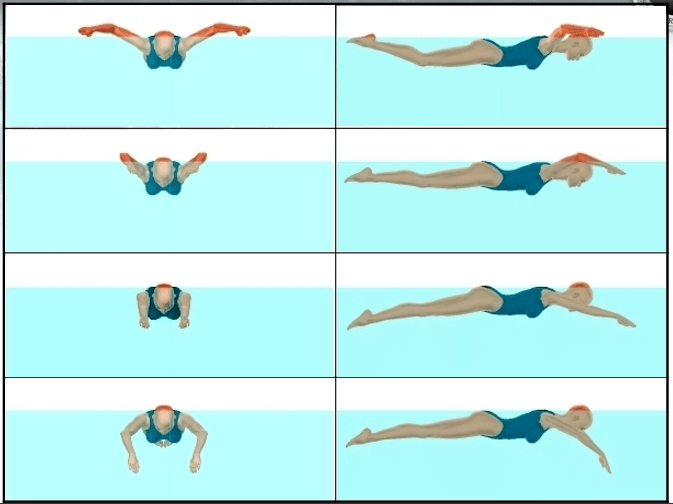

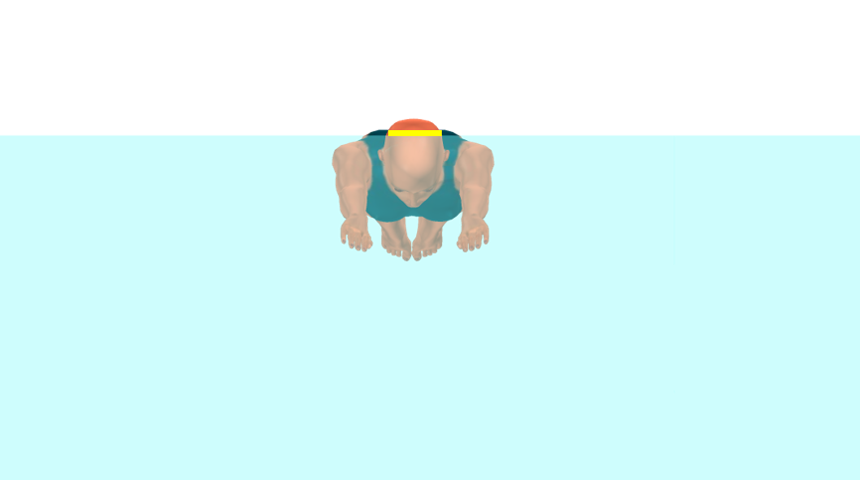

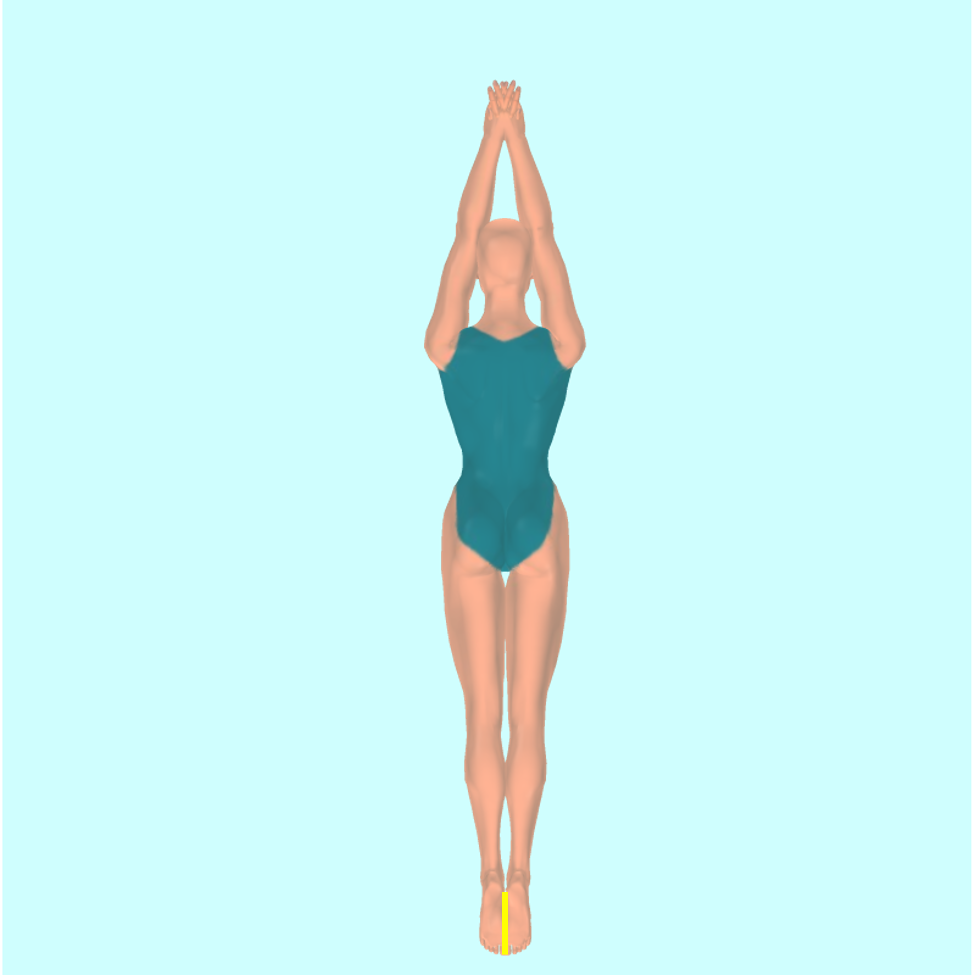

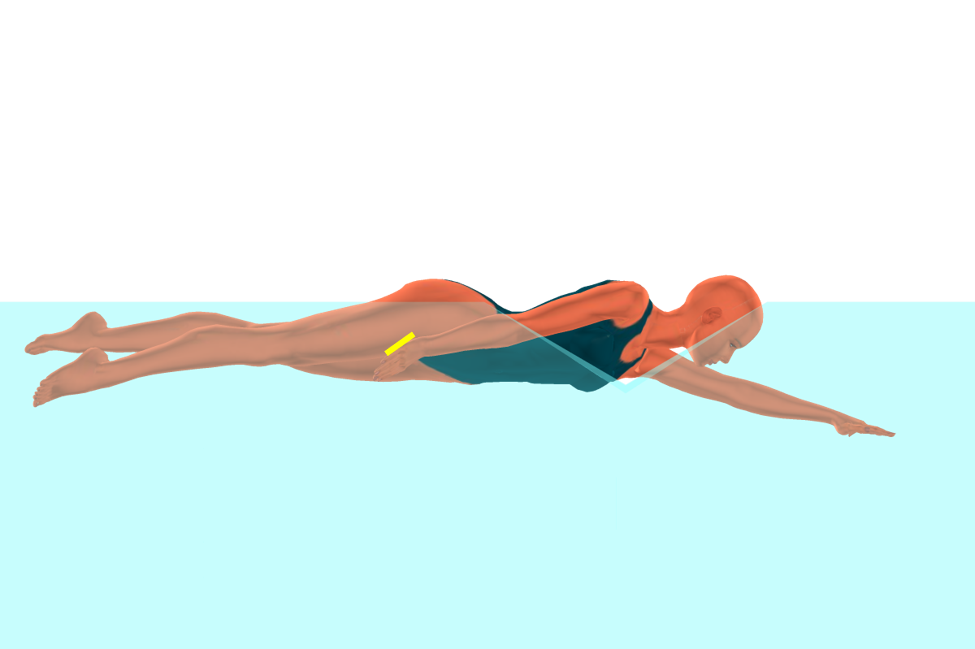

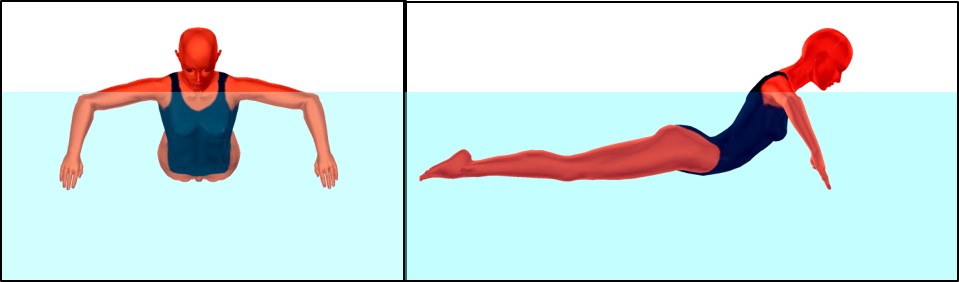

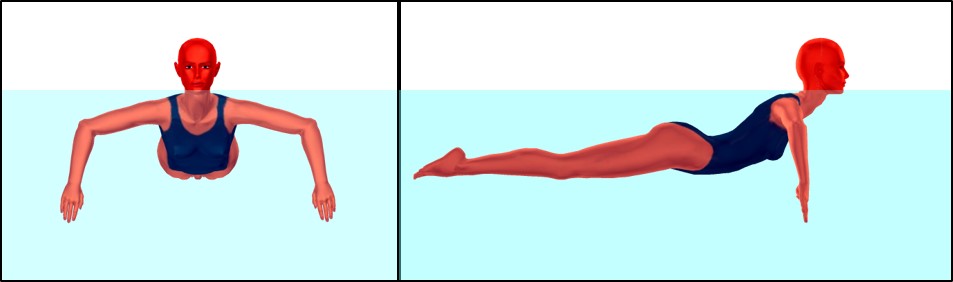

Every week – including during Trials – you can find print and video images of swimmers who either are in – or will soon be in- excruciating pain because they have dropped their heads below the plane of their shoulders. (The image below is of butterfly technique.) Why would anyone think this position could be advantageous? Of course it isn’t: it increases drag, causes shoulder impingement, and makes breathing far more difficult.

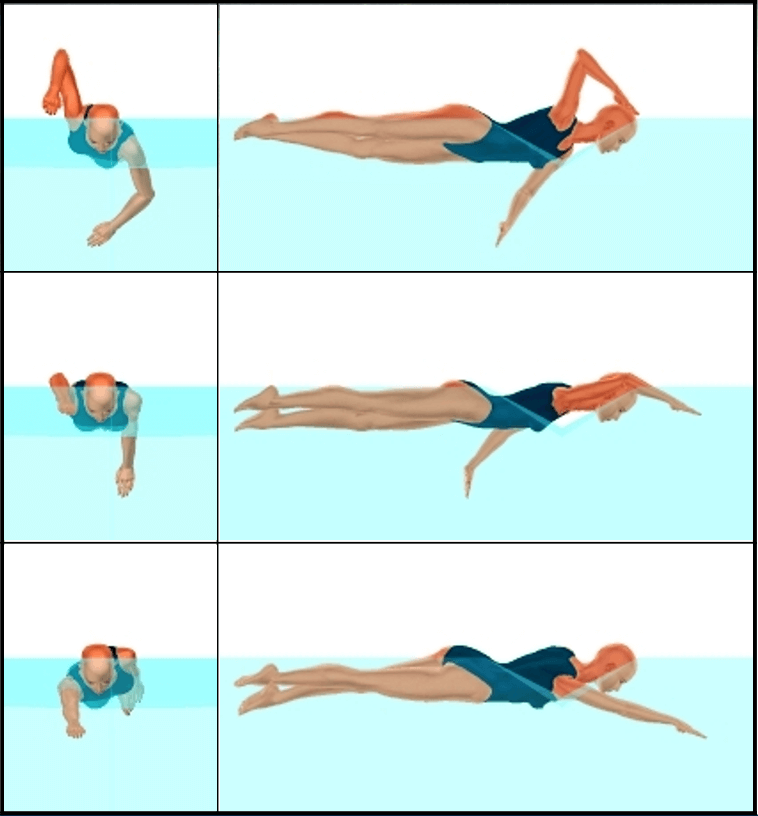

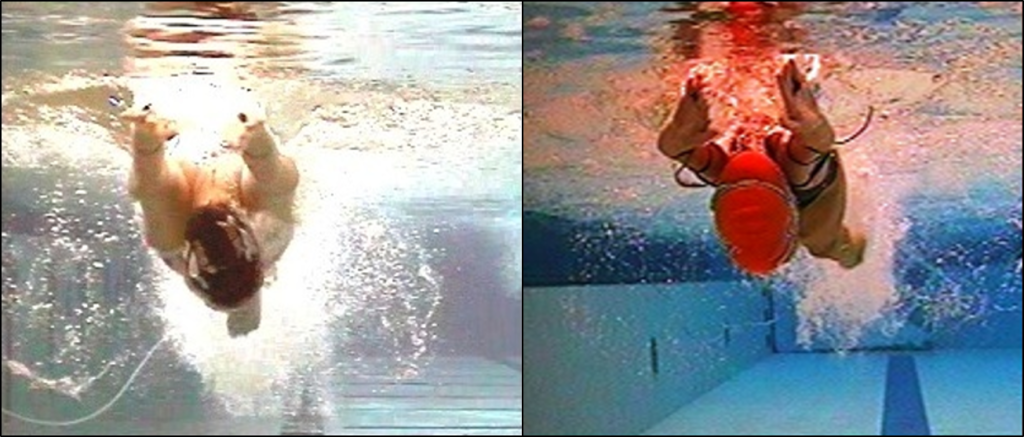

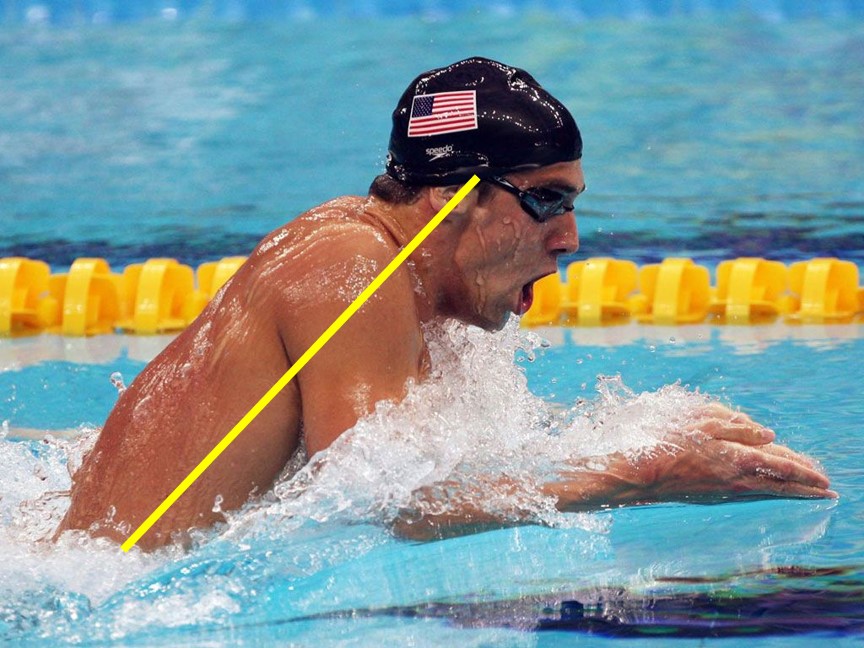

3. Drop the attitude.

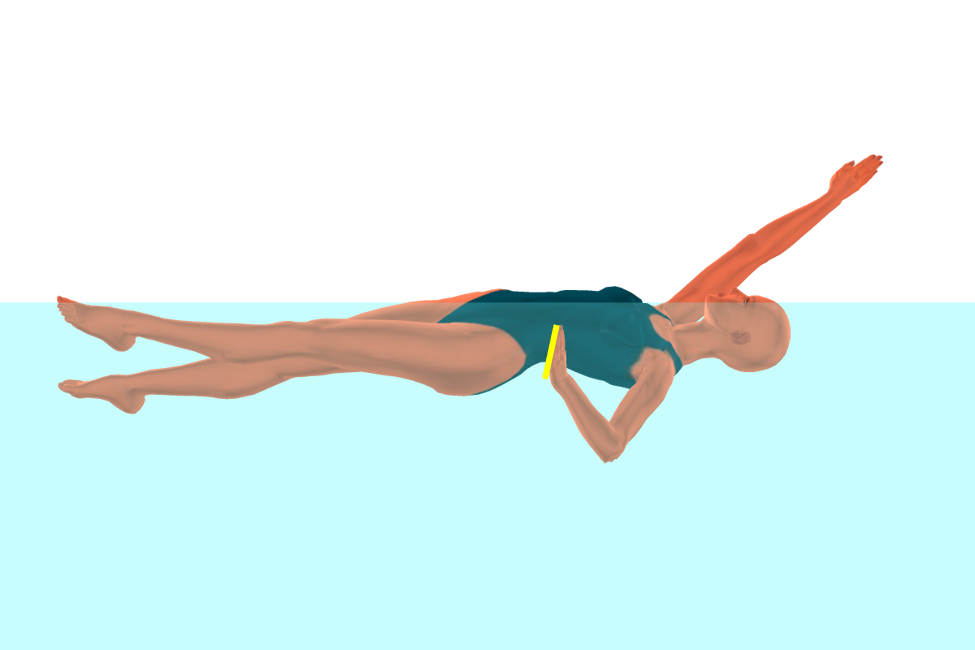

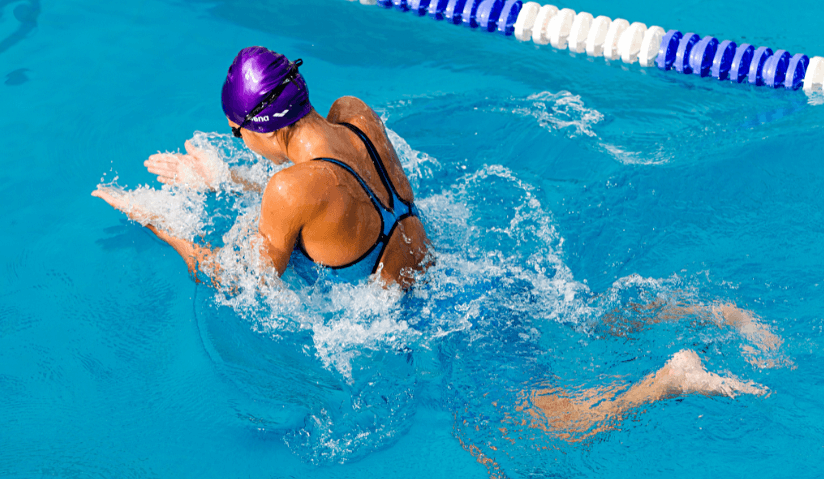

Actually, this one should be drop the altitude. Swimmers who come up this far out of the water on every breathing stroke are doing several technique no-no’s. The near-vertical position increases drag. (As anyone who ever held their hand out of a car window and noticed the resistance difference for a hand held vertically vs horizontally could tell you.) It exaggerates the up and down motion of each stroke – and that excess motion slows you down. (Simple physics tell us that the shortest distance between two points is a straight – not undulating – line. All that up and down adds time to every stroke.) While some vertical motion is inevitable, swimmers who are able to minimize this on both breathing and non-breathing strokes will have a time and energy advantage.

4. Practice makes perfect.

While this may be somebody’s rational for mega yardage, distance actually has very little to do with perfecting technique. UNLESS the swimmer (golfer, runner, tennis player, etc.) is practicing effective technique they might as well be doing any strength/cardio/endurance activity. The practice that makes perfect is focused on a single technique element at a time, is accompanied by immediate feedback and adjustment, and stops when the technique can no longer be maintained at the chosen speed. (10,000 hours of doggie paddle will not make you a better competitive swimmer!) If you want to improve your stroke, you need to first identify what needs to be adjusted, learn exactly what you need to do to adjust, and practice that adjustment at slow speed until it becomes automatic. This expression needs to be “Practice perfect to make perfect!”

5. Knowledge is Power.

The first step toward improvement – for anything – is to identify what needs to change. Once we know that, we can begin the work to improve. Swimmers have a number of ways to identify needed technique changes. First and most important, a coach can observe a swimmer and quickly identify needed changes for most of the basics and some of the advanced elements of stroke technique. At first those technique elements may be simple, like perfecting breathing on both sides in freestyle or keeping the water level at the hairline. At some point, however, every elite swimmer will need ever-smaller and more difficult-to-accomplish adjustments. Those adjustments demand better and more accurate diagnosis tools and expertise. (Underwater video and force analysis are tools that some coaches and scientists are now regularly using.) This is also why it is so dangerous and discouraging to model technique after anyone else. (I personally know a talented high school runner who was sidelined for a significant portion of his junior year after “adjusting” his technique in an attempt to mimic his running idol.)

So, just one question: when is the best time to take mom’s advice?

Now!